The Fiery Story of English Mustard: From Durham to Your Table

When it comes to traditional British condiments, few are as instantly recognisable as English mustard. Famous for its searing heat and bright yellow colour, it has become a staple at Sunday roasts, summer picnics, and pub lunches. But the story of English mustard is more than just food—it’s a tale of innovation, industry, and royal approval that began in Durham in 1720.

Early Mustard in England: From Rome to the Middle Ages

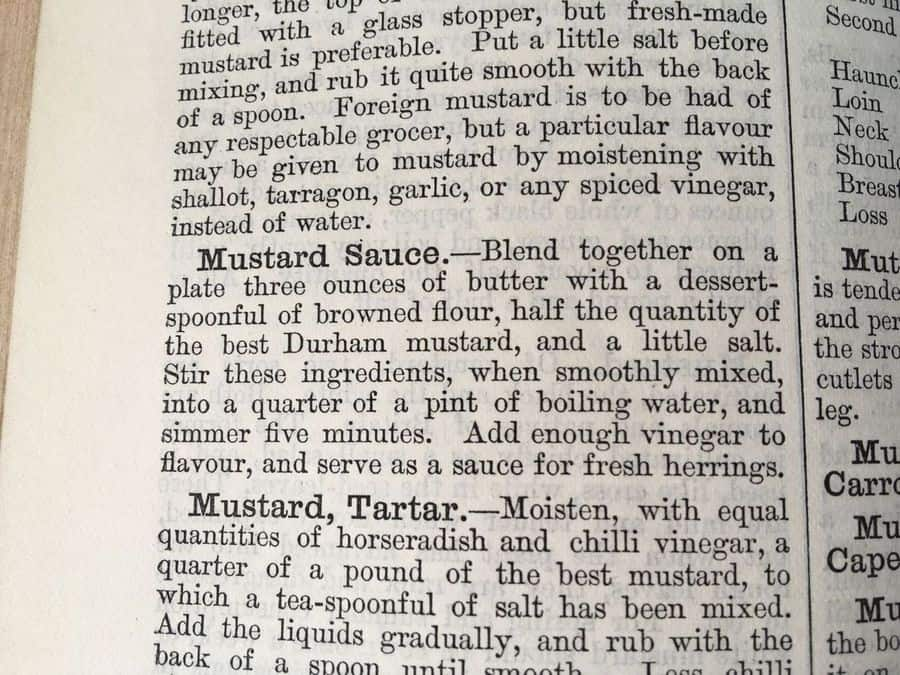

Mustard has been used for thousands of years. The Romans first brought mustard seeds to Britain, mixing them with wine and vinegar to create a pungent sauce. By the medieval period, mustard was widely eaten in England. Monasteries even grew mustard seeds in their gardens, using them to flavour meat and fish during Lent.

However, before the 18th century, English mustard was coarse and mild. It was sold in lumps or balls made from crushed seeds, flour, and spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, or cloves. These additions muted the natural heat of the mustard seed.

What we now think of as “English mustard”, smooth, powerful, and sinus-clearing, did not exist until Mrs. Clements of Durham made her breakthrough.

Mrs. Clements’ Breakthrough in Durham

In 1720, Mrs. Clements of Durham discovered a method that transformed mustard-making forever. By removing the husks and grinding mustard seed into a fine powder, she unlocked its fiery flavour in full. Using milling techniques borrowed from flour production, she created Durham Mustard. Hotter, smoother, and stronger than anything seen before.

The result was a fine, golden powder with a strength and flavour unlike anything before. This was not just mustard—it was Durham Mustard.

Royal Approval: From Durham to London

Like many great British food stories, success hinged on royal attention. On a visit to London, Mrs. Clements managed to present her mustard to King George I. The King was impressed, and soon her fiery powder was in demand among aristocrats eager to follow royal taste. In the 18th century, royal approval was the ultimate endorsement, acting like today’s celebrity chef seal of approval.

Her reputation spread quickly. Durham farmers profited from cultivating mustard as a cash crop, while potters in Gateshead thrived producing the earthenware jars used for storage and distribution.

A Closely Guarded Secret

Mrs. Clements kept her process secret as long as possible, but eventually competitors learned her methods. Her family business passed to her son-in-law, trading under the name Ainsley’s, before being acquired by Colman’s of Norwich in the 19th century.

From Durham to Norwich: Colman’s Mustard

In 1814, Jeremiah Colman established his mustard works in Norwich. By blending white mustard seed (milder) with brown mustard seed (hotter), he perfected a recipe that balanced fire with flavour. Colman’s built a mustard empire, exporting across the world, and became a symbol of Victorian industry and British taste.

To this day, Colman’s packaging carries the famous yellow label and bull’s head logo—not just any bull, but the Durham Ox. This emblem pays tribute to mustard’s birthplace and Mrs. Clements’ pioneering work.

Mustard: More Than Just a Condiment

Part of mustard’s enduring success lies in its versatility. Beyond serving alongside beef, ham, and sausages, mustard has long been prized for its medicinal uses. In the 18th and 19th centuries, mustard plasters were applied to treat chest infections, and mustard seeds were even used as a digestive aid. Today, English mustard remains one of the hottest prepared mustards in the world, with a distinctive heat that clears the sinuses in seconds.

A Lasting Culinary Legacy

What began in Durham’s Saddler’s Yard in 1720 reshaped British eating habits. Mrs. Clements – the “Mother of Mustard” – took a humble seed and transformed it into a national icon. Her fiery innovation turned mustard from a coarse medieval paste into a modern table essential, one that still brightens roast dinners, sandwiches, and picnics three centuries later.

Every spoonful of English mustard carries with it a story of invention, tradition, and regional pride, a legacy as bold and fiery as the condiment itself.